Bonjour / Hello [nickname_else_first_name]

Table of contents

1) Perashat Hashavoua - Rabbi Eli Mansour

2) Halakhat Hashavoua (Halakhot related to day to day life) By Hazzan David Azerad

Shabbat times -Peninei Halacha

3) Holy Jokes!

4) For KIDS

This Week's Parasha Insight with Rabbi Eli Mansour

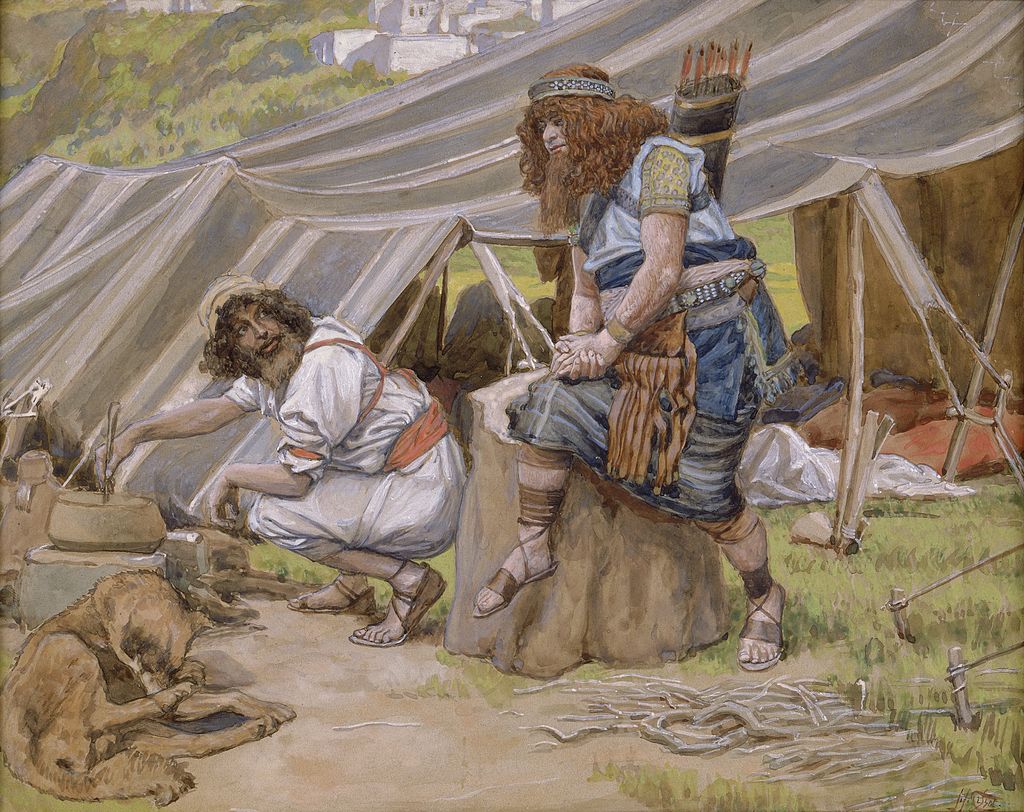

Parashat Toledot: The Obstacle to Parnasa

The Torah in Parashat Toledot tells of Yishak’s struggles as he and his servants tried finding sources of water. After his servants dug and discovered a well of fresh water, the local Pelishtim fought over it and claimed it was theirs. Yishak therefore named the well "Esek," which denotes struggle and troubles. This happened a second time after Yishak’s men found another well, and so he named that well "Sitna" ("hatred"). Finally, they discovered a third well which was not contested. Yishak then proclaimed, "Ata Hirhiv Hashem Lanu U’farinu Ba’aretz" – meaning, now that there was peace, they could grow and prosper in the land (26:22).

Yishak’s proclamation teaches us a fundamental lesson about the dangers of Mahloket (fighting), namely, that it denies us the ability to succeed and prosper. We know that the Torah could not be given until Beneh Yisrael encamped at Mount Sinai "as one person with one heart," as Rashi comments (Shemot 19:2). The spiritual effects of Torah are blocked by strife and discord, and so unity and peace are necessary prerequisites for Torah. Here in Parashat Toledot, we learn that material success is also impossible without unity and harmony. Indeed, the Rabbis teach, "Mahloket Ahat Doheh Me’a Parnasot" – a single fight can cause one to lose one hundred opportunities to earn a livelihood. As we all know, opportunities to make money are rare and hard to come by. Every time we get ourselves into a fight, we deny ourselves dozens of valuable opportunities that we would otherwise have had to earn a comfortable living. Such is the destructive power of Mahloket.

In fact, Rav Haim Palachi (Turkey, 1788-1869) stated that during the period of the revolt led by Korah against Moshe Rabbenu in the desert, the manna did not fall. The Mahloket that raged at that time blocked the pipelines of material blessing, so-to-speak, and so Beneh Yisrael were denied their livelihood. As long as Beneh Yisrael were mired in strife, they could not receive their sustenance. And this is true not only in the desert, but at all times, including now.

One of the Satan’s "tricks" is to convince us that we need to fight and argue in order to get our way and obtain what we want. He has us believe that if we remain silent, if we humbly ignore insults or wrongs committed against us, then we put our wellbeing risk. But the truth is just the opposite. It is fighting and hatred that puts our wellbeing at risk. Our Sages teach that friendship and harmony among people is effective in reversing harsh decrees and in transforming the divine attribute of judgment into the attribute of kindness. The best thing we can do for ourselves, both in terms of Parnasa and in terms of our spiritual achievements, is to live in peace and harmony with the people in our lives. And this requires being forgiving, patient and tolerant, and avoiding arguments and fights even when we are sure that we are right. We must remind ourselves that each time we withdraw instead of arguing, we are opening the gates to Hashem’s blessings and helping to ensure that they will be bestowed upon us and our families.

Halachot this week are selected and Translated by Hazzan David Azerad

Shabbat times -Peninei Halacha

In the Torah, night precedes day for all matters. This is derived from the description of the world’s creation, about which the Torah states: “And there was evening and there was morning, day one” (Bereishit 1:5). This tells us that each 24-hour day begins at night, and thus Shabbat, the seventh day, begins at night. An important concept is enfolded within this Jewish outlook – night and darkness precede day and light. First questions and dilemmas arise, and one is mired in darkness and uncertainty, but from this, answers emerge and light shines upon him. This is also true of our history. At first, we were enslaved to Pharaoh in Egypt, but from there, we were freed, received the Torah, and entered Eretz Yisrael. This is how it always is for the Jewish people – darkness and troubles are followed by light and redemption. First, we must deal with our problems, but from within them we are elevated and refined.

In contrast, when it comes to the nations of the world, day precedes night. Nation after nation ascends the stage of history, makes a vast noise, and shakes up the world. But when difficulties arise and problems begin, the night draws nearer, and finally the nation declines and disappears. It happened to the Babylonians, the Persians, the Greeks, and the Romans. The secret of Jewish immortality is connected to the fact that for us, the night precedes the day.

Since the night precedes the day, the seventh day begins at the beginning of the night. But the Sages were uncertain as to exactly when night begins. Is it when the sun sets and is no longer visible to us, or is it when it becomes dark and three medium-sized stars can be seen in the sky? In other words, are day and night defined by the sun or by light? In Eretz Yisrael, about twenty minutes separate sunset and the emergence of the stars, though this interval fluctuates based on the time of year and the particular locale’s elevation above sea level.

Another unique feature of Judaism is that not every question has an absolute answer. Doubt and uncertainty occasionally play a role, and the present halakha is an example of this. The time between sunset (shki’at ha-ĥama, or “shki’a”) and the emergence of stars (tzeit ha-kokhavim, or “tzeit”) is classified as a time when it is uncertain whether it is day or night and is called “bein ha-shmashot.”

In practice, for all Torah laws, including Shabbat, we follow the well-known principle: “Safek de-Oraita le-ĥumra,” that is, we rule strictly when in doubt about Torah law. Therefore, Shabbat begins at shki’a and ends at tzeit.

Bevirkat Shabbat Shalom Umevorach

David Azerad

3) HOLY JoKeS!!

Selection of funny snippets, loosely related to this weeks parashah or current events, to brighten your day

4) FOR KIDS

4) FOR KIDS

Click on the image above to open the youtube video

TOLDOT Arts & Crafts (click on image to go to site)

4) FOR KIDS

4) FOR KIDS