Bonjour / Hello [nickname_else_first_name]

Table of contents

1) Perashat Hashavoua - Rabbi Eli Mansour

2) Halakhat Hashavoua (Halakhot related to day to day life) By Hazzan David Azerad -

The Mechanics of Counting - Peninei Halach

3) Holy Jokes!

4) For KIDS

This Week's Parasha Insight with Rabbi Eli Mansour

Parashat Ahare Mot/Kedoshim: Keeping Hashem’s Presence Among Us

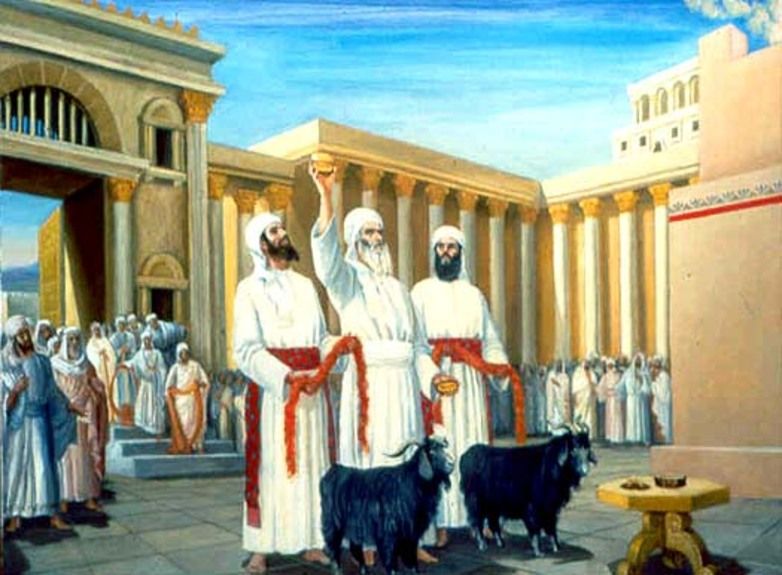

The Torah in Parashat Ahareh-Mot (18:21) commands, "Do not give over any of your offspring to be passed to Molech." As Rashi explains, "Molech" was a cruel pagan ritual whereby parents would bring their child to a priest who then passed the child through fire, burning him alive. The Torah returns to this subject later, in Parashat Kedoshim (20:1-5), where it says that practicing the Molech ritual is punishable by death, because a person who gives his child to Molech has the effect of "defiling My Sanctuary" ("Tameh Et Mikdashi").

The obvious question arises, while we clearly recognize the grievousness of such an act – killing one’s child as a religious ritual – how does this have the effect of defiling the Bet Ha’mikdash? What does the Bet Ha’mikdash have to do with the Molech ritual?

Rav Abraham Saba (1440-1508), in his Seror Ha’mor commentary, explains that people would bring their children to Molech because they felt that offering animal sacrifices is not a sufficient expression of submission and subservience to G-d. Such people show disdain for the Bet Ha’mikdash, figuring that the sacrifices offered there are inadequate. Therefore, they indeed "defile" the Bet Ha’mikdash, in that they look down upon the service performed there and insist that they need to do something else that they feel is better.

Rashi, however, explains differently. He writes that the word "Mikdashi" in this verse refers not to the Bet Ha’mikdash, but rather to the Jewish Nation, which is, in Rashi’s words, "Mekudeshet Li" – "sacred to Me." Sacrificing one’s child to Molech, according to Rashi, defiles not the Bet Ha’mikdash, but rather the Jewish People.

The Ramban (Rav Moshe Nahmanides, Spain, 1194-1270) elaborates further on this concept. He cites a comment in the Midrash that if one eats without reciting a Beracha, he steals not only from G-d – who owns the entire universe, and from whom we must thus request permission before deriving benefit from the world – but also from the Jewish Nation. The Ramban explains that by reciting a Beracha, we contribute to the presence of the Shechina in our world. When we recite a Beracha, acknowledging that G-d is the source of everything we have in this world, we add to His presence among us. And so when we fail to recite a Beracha, the Ramban explains, we cause the Shechina to leave the world, to some degree, and in this sense, we "steal" from Am Yisrael, diminishing from G-d’s presence among us. The Ramban adds that if a person takes his most precious possession of all, his child, and sacrifices him to Molech, instead of raising him as a loyal member of our nation who faithfully serves Hashem, he causes the Shechina to depart, and in this sense, he "defiles" the Jewish Nation, leaving them bereft of G-d’s presence.

While at first it might appear that this law has no relevance to us today, as nobody would ever imagine offering their child as a sacrifice, in truth, this law conveys a vitally important message for us even now. The "Molech" of our day and age is the culture of the society around us. This culture is like fire, as it "consumes" a child’s spiritual spark, his potential for Kedusha. Parents who fail to provide their children with a strong Torah education in effect surrender them to the modern-day "Molech," to the spiritually destructive forces of the society. This harms not only the children themselves, and not only the family, but all Am Yisrael. The entire Jewish Nation is affected when a precious child’s spiritual potential is "burned" and lost to us. Parents bear an obligation not only to their children, and not only to themselves, but to all Am Yisrael, to raise their children according to our sacred tradition so they can fully maximize their potential and do their part to keep Hashem’s presence among us.

Halachot this week are selected and Translated by Hazzan David Azerad

Customs of Mourning During the Omer Period - Peninei Halacha

The days between Pesach and Shavu’ot are days of sorrow because 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva died then. Therefore, we observe some customs of mourning during this period: postponing marriages, refraining from taking haircuts, and avoiding dancing unless it is for the sake of a mitzvah.

Before discussing the details of these customs, it is fitting to expand a bit upon the main point, which is why R. Akiva’s students died. The Talmud states in Tractate Yevamot (62b): “Rabbi Akiva had 12,000 pairs of students… and they all died during the same period, because they did not treat each other with respect… It is taught in a bereita, ‘They all died between Pesach and Atzeret (Shavu’ot)’… They all died an evil death. And the world was desolate, until R. Akiva came to our Rabbis in the South and taught them (and these are the new students): R. Meir, R. Yehudah, R. Yosi, R. Shimon, and R. Elazar son of Shamu’a; and they established the Torah.” The Midrash (BeReishit Rabbah 61:3) further recounts that R. Akiva said to his new students, “My sons, the first ones died only because they begrudged one another; make sure not to do as they did.”. They died at the time of the Bar Kochva rebellion. Some students went out to fight the Romans, while others continued studying Torah, and the two groups denigrated one another, saying: “I am greater than my colleague, for my contribution is important and beneficial, while my friend’s is useless.” Because of this baseless hatred, they were defeated by their enemies, which explains why they all died around the same time. Indeed, the date is not coincidental – between Pesach, which represents Jewish nationalism, and Shavu’ot, which symbolizes the celestial Torah. By showing disrespect for one another, these students separated between the holiday of Pesach and that of Shavu’ot, between nationalism and Torah, causing them all to die during this season. Some quote the passage from BeReishit Rabbah as follows: “They begrudged one another’s Torah.” According to this, the primary rectification needs to be directed towards increasing respect between the Torah scholars of the different camps. (See below, end of note 13, [where we explain] that these days have a festive side, as well, serving as a chol ha-mo’ed [of sorts] – intermediary days between Pesach and Shavu’ot.) ]

Since then, we observe some customs of mourning and try to improve our interpersonal relationships, especially those between Torah students, during the period of Sefirat HaOmer. And since this is based on Jewish custom, not an explicit Rabbinic enactment, there are different customs among the various communities, as we will explain below.

Around a thousand years later, during the Crusades that began in 4856 (1096), the Christians slaughtered tens of thousands of Jews in Germany. These tragedies also occurred mainly during the days of the Omer. Approximately five hundred years later, from 5408-5409 (1648-49), terrible massacres befell the Jews once again, this time in Eastern Europe. Tens, and perhaps even hundreds, of thousands of Jews were murdered. These pogroms also occurred, for the most part, during the Omer period. Therefore, Ashkenazi Jews are inclined to rule more strictly regarding these customs of mourning.

Bevirkat Shabbat Shalom Umevorach

David Azerad

3) HOLY JoKeS!!

Selection of funny snippets, loosely related to this weeks parashah or current events, to brighten your day

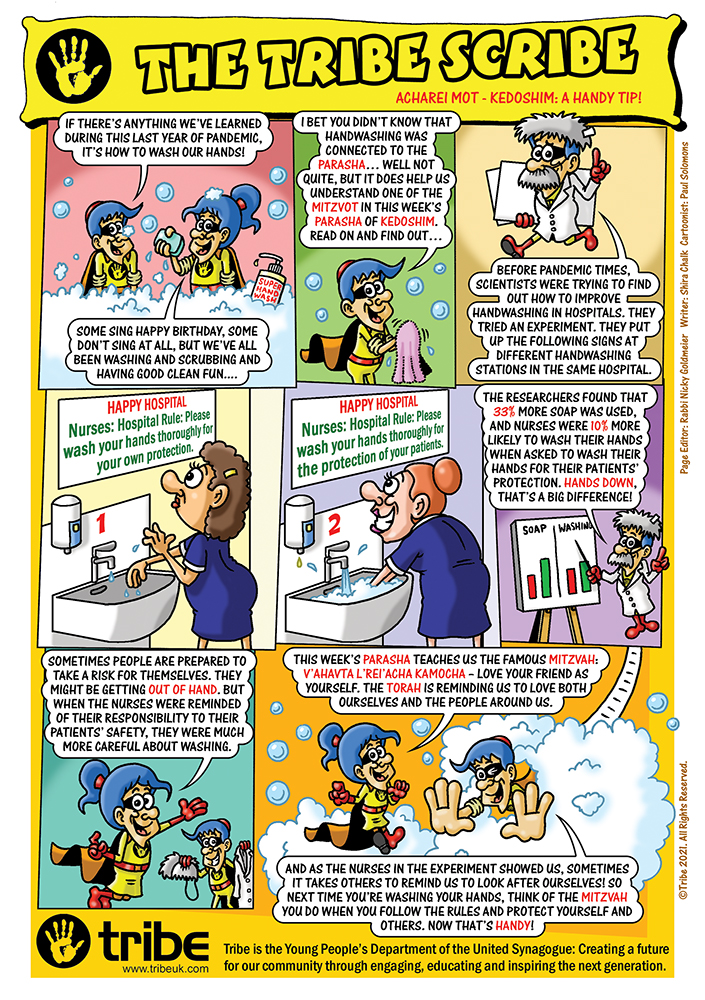

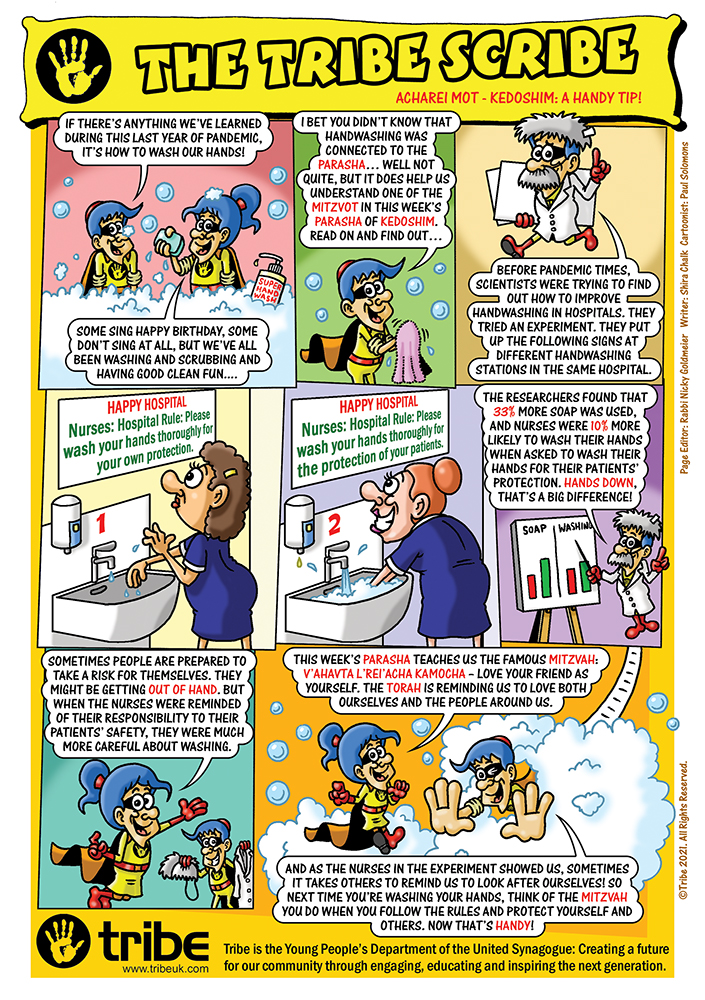

4) FOR KIDS

Click on the image to open the youtube video