Bonjour / Hello [nickname_else_first_name],

Table of contents

1) Perashat Hashavoua - Rabbi Eli Mansour

2) Halakhat Hashavoua (Halakhot related to day to day life) By Hazzan David Azerad -

Zakhor and Shamor - Peninei Halacha

3) Holy Jokes!

4) For KIDS

This Week's Parasha Insight with Rabbi Eli Mansour

Parashat Re'eh- Judaism is Not a Supermarket

**This week's Parasha has been dedicated L’iluy nishmat Natan ben Shoshana HaLevy by his children.

The Torah in Parashat Re’eh speaks of the Misva of giving charity, in several different contexts. One of the intriguing features of this Misva is the unusual repetitive form that the Torah uses in presenting this Misva. It instructs, "Aser Te’ser" ("You shall surely tithe" – 14:22); "Patoa’h Tiftah Et Yadecha" (You shall surely open your hand" – 15:8); and "Naton Titein" ("You shall surely give" – 15:10).

The simple explanation for this repetitive form is that we naturally feel a degree of hesitation and reluctance to part with our hard-earned assets. Earning a living is difficult, and many people live in a constant state of anxiety about finances – making them feel ambivalent about giving charity, even if they sincerely want to assist those in need. The Torah therefore formulates its commands of charity with special emphasis, recognizing that people need an extra "push" when it comes to making charitable donations.

However, some have suggested an additional interpretation.

Many times, we are moved and inspired to give due to our feelings of compassion for those in need. When we see an emaciated, disheveled pauper in tattered clothing, we naturally feel pity and genuinely desire to help. When we attend a fundraiser and hear about the plight of the people in need of help, we are emotionally stirred and roused to write checks. This is, without question, admirable, and those who give out of compassion and pity are worthy of our respect. But the Torah is indicating to us that there is an additional component to giving charity – simply to fulfill G-d’s command of Sedaka. We are to give not only out of our natural feelings of compassion for the recipient, but also to obey G-d’s command. Giving out of compassion is certainly a Misva – but we must give also out of a sense of strict obedience to Hashem who commanded us to give.

There are lofty intentions that we can have when performing a Misva. They are all precious and valuable, as long as we don’t forget the most basic and important intention – that we perform the Misva because Hashem commanded us to.

The Gemara in Masechet Yoma tells of a woman named Kimhit, who had seven sons who all served as Kohen Gadol in the Bet Ha’mikdash. The Rabbis asked her what she did to deserve this special distinction, and she replied that she conducted herself with exceptional modesty. The Gemara then tells that many other women followed her modest practices, but did not receive such great reward. The Ben Ish Hai (Rav Yosef Haim of Baghdad, 1833-1909), in his work Ben Yehoyada, explains that the other women did not receive such great reward because they conducted themselves this way in order to earn the reward. After hearing about how Kimhit was rewarded for her special level of modesty, they wanted to do the same – in order to earn that same great reward, and for this very reason, the reward did not come. As the Mishna in Abot famously teaches us, we are to serve Hashem without expectation of reward. Our primary intention must be to serve Hashem, to fulfill His will. The fact that a Misva is Hashem’s will should be enough of a reason to perform the Misva.

Some people approach Judaism as though it is a supermarket: they go in for the purpose of getting what they want. They perform Misvot so that Hashem will grant them the things they desire in life – wealth, health, successful children, and so on. But this is a very juvenile – and distorted – perception of Torah life. G-d does not owe us anything, no matter how many Misvot we observe. We are His servants; He is not our servant. We are to feel privileged and fortunate to fulfill the will of the King of kings, to have been chosen as His special servants. This should be all the motivation we need to fulfill the Misvot.

As in the case of Sedaka, there might be different reasons why we want to perform a certain Misva, and some of them may even be legitimate and noble. But we must never forget that the most important reason is simply the fact that Hashem commanded us to perform Misvot. This is all the motivation we need to obey His will.

Halachot this week are selected and Translated by Hazzan David Azerad

Zakhor and Shamor - Peninei Halacha

Two mitzvot constitute the basic elements of Shabbat: Zakhor (“commemorate”) and Shamor (“observe”). “Shamor” is a negative commandment to refrain from all labor. For six days, one must take care of his needs and productively engage the world, but on Shabbat we are enjoined to desist from all labor. By doing so, we clear space in our soul, which we are commanded to fill with the positive mitzva of Zakhor, whose content consists of commemorating the holiness of Shabbat and using it to connect with the fundamentals of faith.

These two mitzvot are so intimately linked that they are united at their root. They split into two complementary mitzvot only upon entering the human realm. This is the meaning of the Sages’ dictum: “Zakhor and Shamor were stated simultaneously, something that the human mouth cannot articulate and the human ear cannot hear” (Shev. 20b). We see this in the Torah itself: the Decalogue as reported in Shemot (20:8) introduces Shabbat with the word “zakhor,” whereas when the Ten Commandments are repeated in Devarim (5:12), it is replaced with “shamor.”

Zakhor is a positive commandment, rooted in love and the divine attribute of ĥesed (kindness). In contrast, Shamor is a negative commandment, rooted in the divine attribute of din (judgment), which sets boundaries so that man may turn away from wickedness. Positive mitzvot are at a higher level, as they enable people to come closer to God. However, the punishment for transgressing a negative mitzva is more severe, because it causes more serious damage, both to the sinner and to the world at large (Ramban, Shemot 20:7).

Zakhor is closely linked to the creation of the world and the first Shabbat, as the Torah states:

Commemorate (“zakhor”) the day of Shabbat to sanctify it…. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth and sea, and all that is in them, and He rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed Shabbat day and hallowed it. (Shemot 20:8-11)

The mitzva of Shamor is more closely linked to the Exodus from Egypt:

Observe (“shamor”) the day of Shabbat to sanctify it…for you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God freed you from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God has commanded you to keep the day of Shabbat.” (Devarim 5:12-15)

As a lofty spiritual principle, Shabbat was embedded in the world at its very creation. However, it was only after Israel survived the iron furnace of the Egyptian enslavement that they could understand how terrible it is to be subjugated to the material and how necessary it is to stop working to absorb the spiritual concept of Shabbat.

The two commandments – Zakhor and Shamor – are hinted at in the word “Shabbat.” Its simple meaning is related to the shevita, cessation of work, associated with Shamor. However, its deeper meaning is related to teshuva, “repentance” or “return,” for on Shabbat we return to the foundations of faith associated with Zakhor.

Bevirkat Shabbat Shalom Umevorach

David Azerad

3) HOLY JoKeS!!

Selection of funny snippets, loosely related to this weeks parashah or current events, to brighten your day

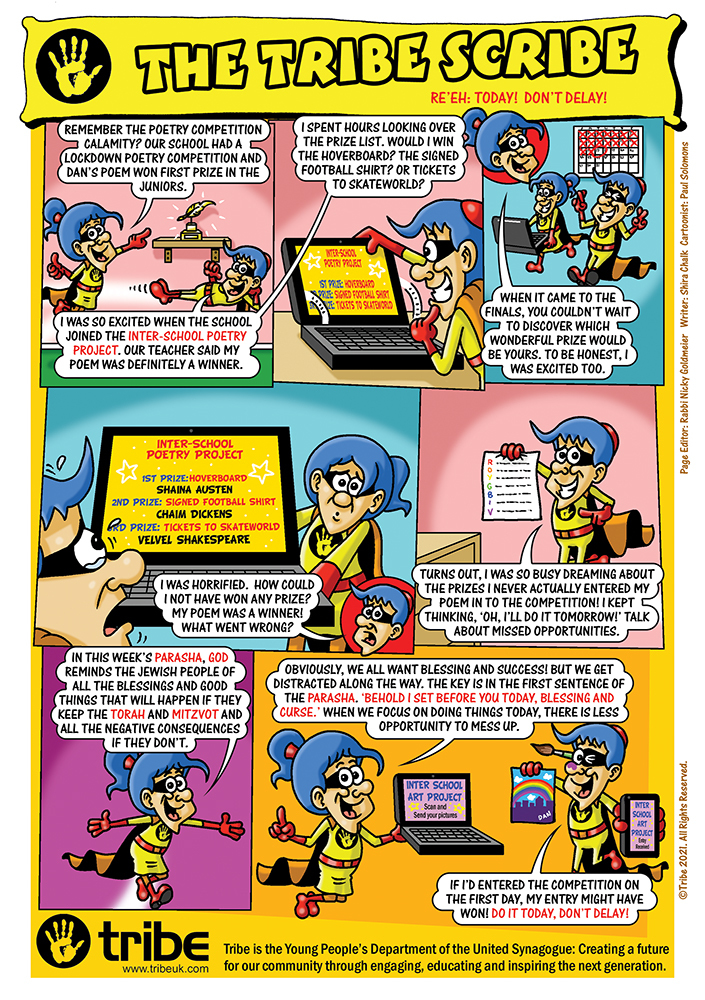

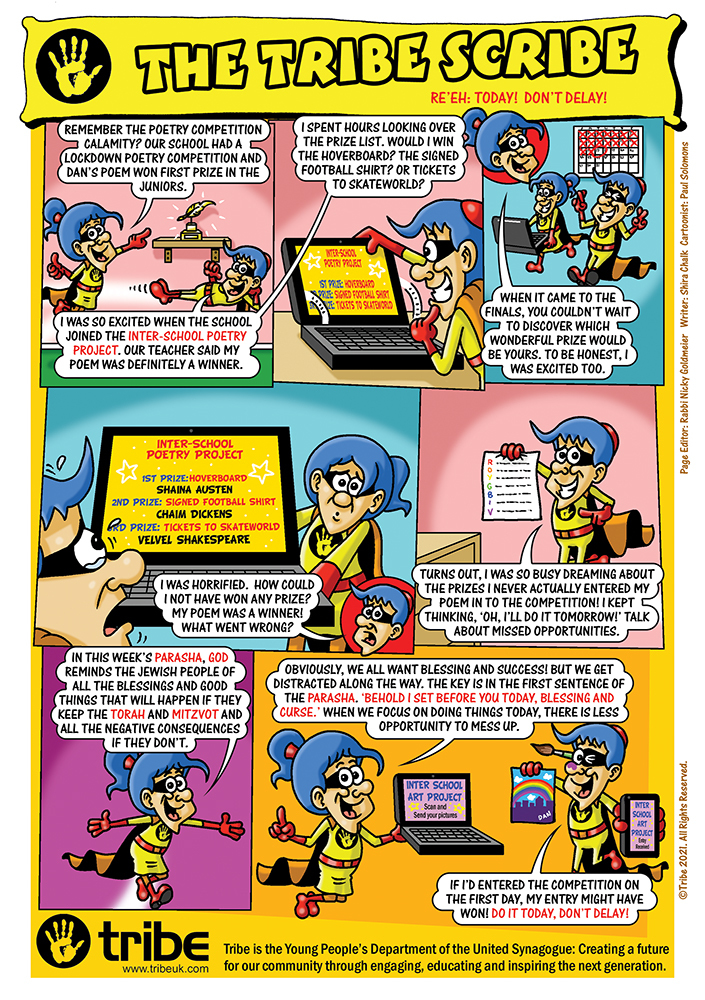

4) FOR KIDS

Click on the image to open the youtube video